The Dark Web

How credit unions can make their members data less valuable on the dark web.

The dark web has been in existence since the 1990’s but has become a household word lately through ads from identity protection companies that offer to monitor the dark web. The ads warn a subscription-paying customer if their data may have been compromised and put up for sale.

The dark web is where fraudsters conveniently sell breached data such as usernames and passwords, credit and debit card data, alongside complete identities, passports, drugs, guns, and worse. The dark web, and the crimes associated with it, is a big and sophisticated business. There are fraudsters that specialize in obtaining the data. There are other fraudsters that specialize in validating the data, using bots to try the usernames and passwords on hundreds of sites, and others that specialize in testing the credit and debit card numbers on unsuspecting ecommerce merchant sites. Downstream, other fraudsters take the useable payment credentials and either create counterfeit cards or launder the card numbers by buying electronics and gift cards through online merchant sites. Still others use the validated usernames and passwords for account takeover fraud, draining bank accounts. These groups buy and sell their data on the dark web, creating an entire economy of fraud, and its thriving. Fraudsters go where the money is. But a new business is also thriving from the same economy – the many services that claim to monitor the dark web on behalf of concerned clients. This is starting to shed light on the dark web, and that is unwanted by the bad guys.

What is the dark web?

To understand how these two business models are at odds, it’s necessary to first understand what is the dark web. It is not a separate network, and it was created by the U.S. government for intelligence operatives (i.e. spies) to anonymously exchange information over the world-wide-web. Just like Napster and Aimster worked over the web to exchange music anonymously by downloading proprietary software for music and movie files to be exchanged, the dark web also requires special software. The software is called Tor and it allows you to navigate websites that are proprietary to the dark web.

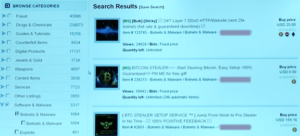

While theoretically anyone can download Tor and start browsing, law enforcement, internet service providers, and the bad guys are all tracking computers that access the dark web. Federal and international security agencies are looking to track activity, while the bad guys will test each new computer that accesses the dark web to see if they can gain access to the camera and laptop, as well as the O/S to install malware. This threat is usually enough of a deterrent that only fraudsters, and security specialists are the ones accessing the content on the dark web. That content is usually in the form of a marketplace, like eBay, with some becoming familiar names, such as Alphabay, Silk Road, Crypto Market, and Hansa. According to the FBI, Silk Road made a total of $1.2 billion between 2011 and 2013 when it was shutdown (although Silk Road later re-emerged). Prices are always posted and transactions are usually conducted in Bitcoin, with some marketplaces accepting other cryptocurrencies. And in an ironic twist, marketplaces allow buyers to post ratings of sellers to weed out the bad sellers from the good ones.

A screenshot from a session provided by Executive Security Advisor of IBM Security, Etay Maor shows one site’s homepage where buyers can choose from “products” ranging from jewels, credit and debit card numbers, gold, drugs, malware and ransomware software, and weapons, as well as services such as stolen credit card laundering, skimming placement and retrieval, and even bomb threat services where the seller will call a school and make a threat in order to get a student out of taking a test.

The marketplaces on the dark web constitute big business, with combined daily volumes that reach $650,000 at peak (averaged over 30-day windows), while researchers say the total is generally stable between $300,000 and $500,000 a day. The companies that monitor the dark web also constitute big business, with examples like Terbium Labs raising $6.4 million in venture capital funding, and Cybersecurity firm FireEye acquiring threat intelligence company iSight Partners for $200 million.

If the dark web is being monitored by good guys, why is it still in business?

The dark web is surprisingly transparent – it’s open to anyone to access, to buy and sell goods and services, and is very efficient at connecting buyers and sellers, albeit for illegal and illicit purchases. If monitoring companies and law enforcement have such easy and open access to this activity, why does it still exist? Three primary reasons: money, anonymity, and a high level of sophistication. The amount of money being transferred over the marketplaces on the dark web dwarf the GDP of most nations, and as long as buyers and sellers can conduct their transactions in the open, but remain completely anonymous and untraceable, then these transactions will continue, and these marketplaces will continue to grow. In an example of how sophisticated these marketplaces are, according to Krebs on Security, one cybercrime marketplace’s own security system triggered a “pig alert” and brazenly flagged the fed’s transactions as an undercover purchase placed by a law enforcement officer.

There is also a timing element to the monitoring activity. In the case of a credit card breach, by the time a monitoring company finds a new batch (or “dump” as they are referred to on the marketplaces) of card numbers for sale, those cards may have already been stolen, possibly counterfeited and laundered. Unlike physical goods, a batch of stolen card numbers can be sold several times.

How can CU’s make member card data less valuable on the dark web?

As long as there is a mag stripe on credit and debit cards, and as long as merchants allow a 16 digit number to be used to make a purchase, there will be card breaches, counterfeit cards , and online card fraud. But there are some definitive steps that credit unions must take to make their members’ data less valuable on the dark web.

- Enable EMV and reissue chip cards. The level of sophistication of the fraudsters should never be underestimated. The bad guys are tracking which BINs have not been enabled for EMV. Those BINS are specifically listed on the marketplace as readily counterfeit-able, and draw a bigger price tag.

- Tokenize BINs and encourage members to use Visa Checkout, MasterPass, or Apple/Samsung/Android Pay when making purchases online.

- Monitor for patterns and be quick to act. Be on the lookout for authorizations with no settlement – that’s a sure sign that bad guys are testing out counterfeit cards before making bigger purchases. Identify enumeration testing, where fraudsters are looking for a good account number, expiration date and cvv2 values.

- As soon as CAMS and ADC alerts are issued by the networks, be quick to shutdown identified cards and notify the cardholders.

- Educate members, continuously, on best practices, such as using credit instead of debit, turning on email and text purchase notifications, and never clicking on links in emails or websites unless they can be completely trusted.

None of these steps by themselves will keep fraud from occurring 100%. However, with a comprehensive fraud management and prevention plan in place, a credit union can help make their member’s data unusable by the bad guys.